Interview with Danish Dance Theatre dancer Julien Guillemard, sharing with DANS his very personal interpretation of Centaur

By Iben Maria Hammer (dance writer, DANS)

Just before initiating the summer vacations in Brittany, the most western part of France, dancer Julien Guillemard shares his thoughts on Centaur with DANS, telling how he came to the Danish Dance Theatre especially to work on Centaur by choreographer Pontus Lidberg.

(a review of Centaur is published in DANS (efterår 2022), the printed magazine)

As a ballet dancer at the Paris Opera, Julien Guillemard met Pontus Lidberg, when the Swedish choreographer was making a piece called Les Noces with the French ballet company back in 2019.

“This is how we met each other and had a discussion about my future. I wanted to leave The Paris Opera –for a shorter period of time at least – because I wanted to explore the world”, Julien explains.

The Paris Opera was Julien’s entire world for twelve years, but he also emphasizes that this training or study in a way is a wonderful key to meet new choreographers and to develop new skills. Yet it can be a source of frustration only being able to work with them for a month or so, before they are gone again.

“I was sharing this with Pontus, and he said that maybe I should come and audition for the Danish Dance Theatre.”

So you auditioned for Centaur and you and Pontus decided to go ahead?

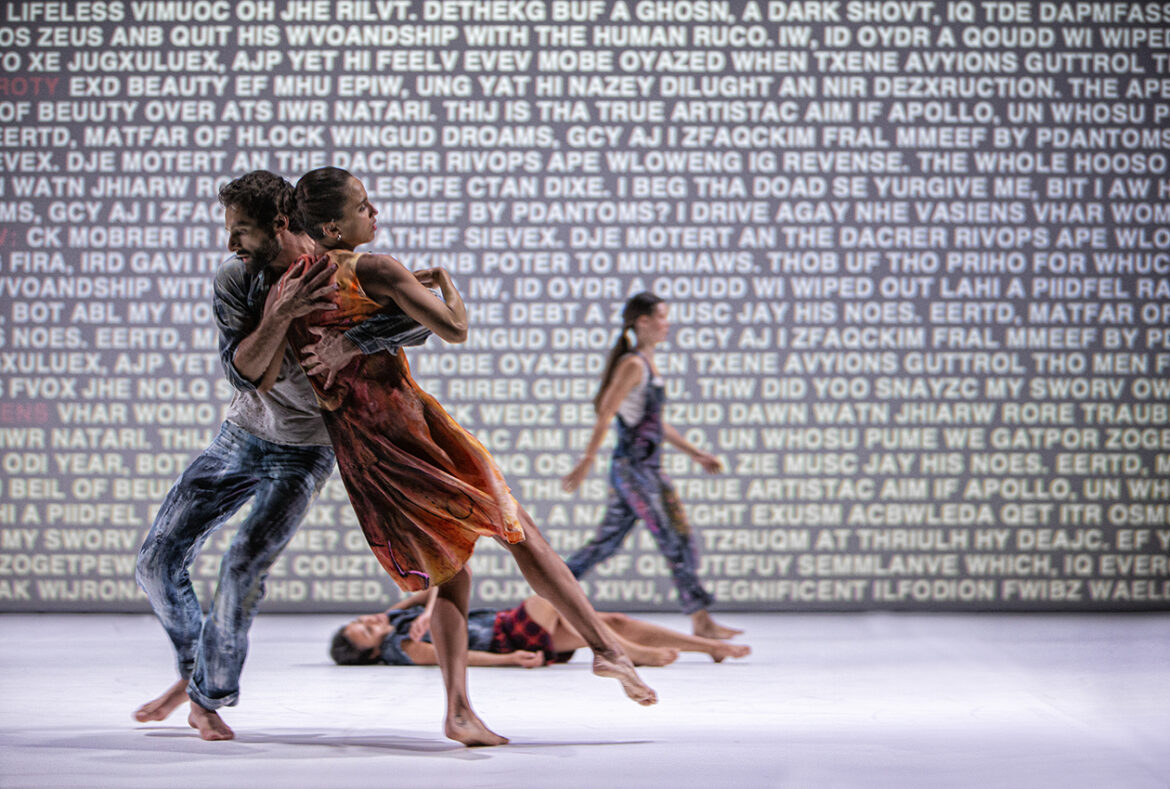

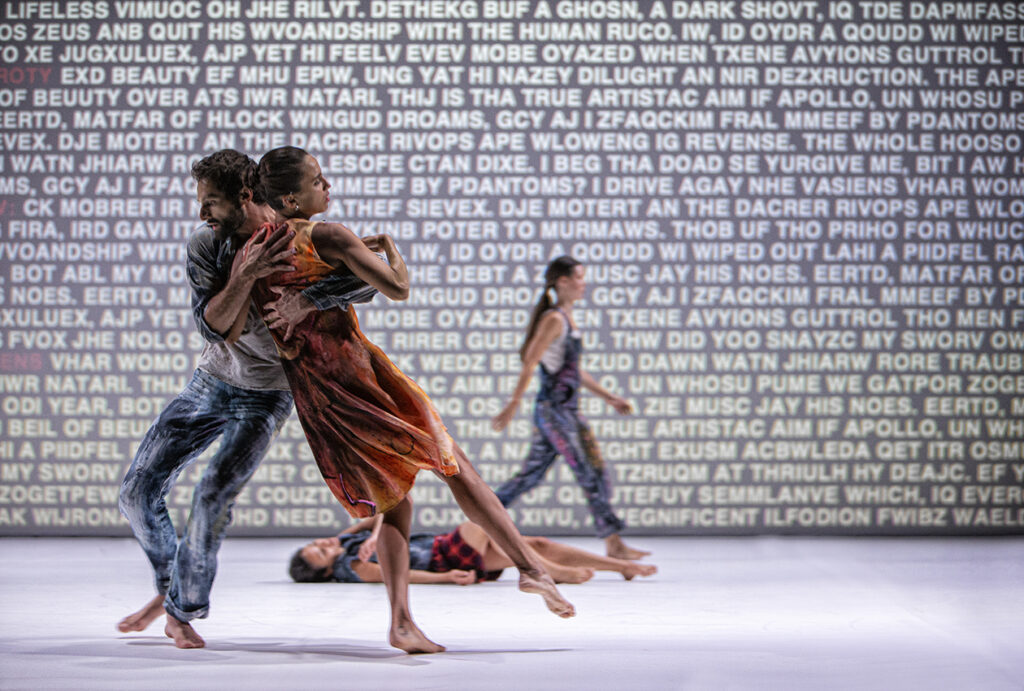

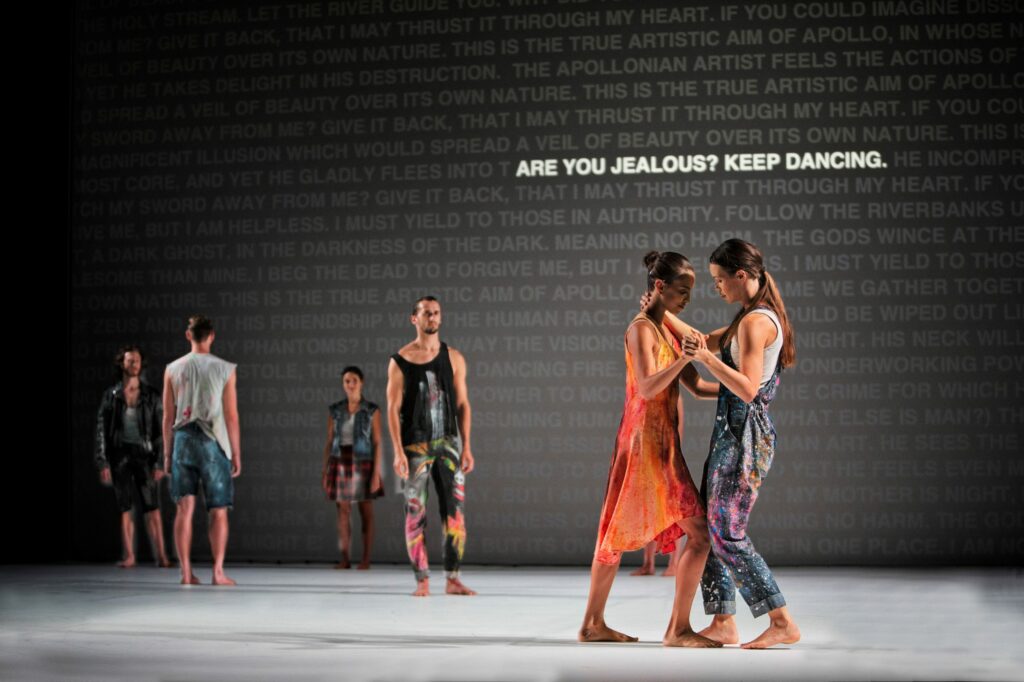

“In the first place, Centaur was supposed to be a collaboration between The Royal Danish Theatre and DDT. Pontus wanted, I think, to use the ballet dancers’ technique on one side, like something more set and therefore more robotic, and the DDT dancers’ on the other side, to create something more human.”

That was the plan, but then Corona happened?

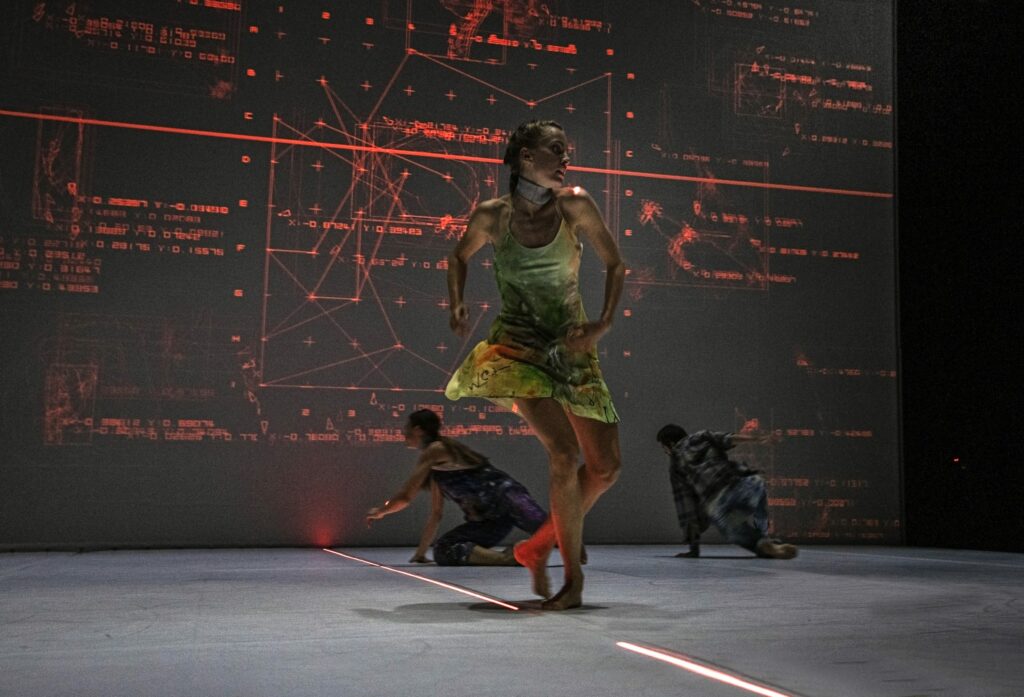

“Yes, and the dancers of The Royal Danish Ballet were suddenly not part of the project anymore, but the thought was still to find in the choreography itself a way to play between those two aspects. Between being programmed and just responding as tools for the AI (Artificial Intelligence; ed.) and then on the other hand using how the AI can reveal also very essential aspects of humanity – and who is controlling who in a way

because the AI is programmed by humans …”

My experience is that it is a kind of a relief sometimes, when the computer system has a breakdown, and we get a pause from the screen with all the coordinates and it becomes more analogue. Your hear music with Shubert, you have a pas de deux, and it gives you the space to breathe a little bit. I suppose that is also a point?

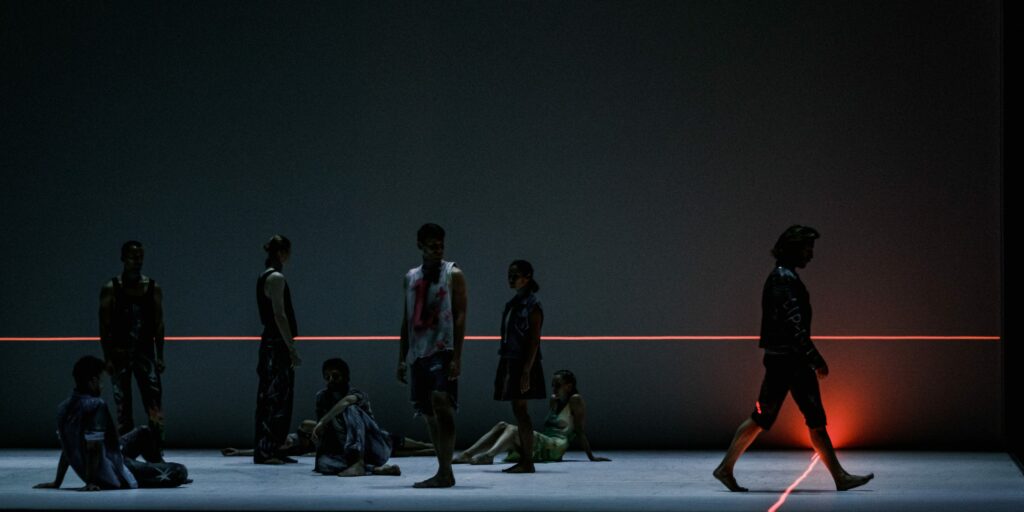

“Yes, exactly, I believe it was a way to play with this tension in a way, when the AI is coming and going. It also left us, dancers, time to breath. Cause when the AI is on, we never really know what we will be asked to do, so there is this tension of just waiting for the AI to decide what we are to do.”

This thing of being scored must also be a sort of pressure?

“Yes, at the very beginning we were really aiming at not to fail at all. But that didn’t really work. Because we are humans, we are not that precise, and therefore sometimes the combinations that the AI was doing with the phrases resulted in us crashing. So we implemented this thing of stopping up, raising our hand, showing that we failed and run to the side.”

Humans versus machine!

“When you as a human are used as a tool, it becomes also a bit dangerous. Like the AI could ask you to do weird stuff, and you would have to do it, because you are on the stage. We are not going so much there, but that could be interesting as well. There is a moment in the beginning, where we have the trackers and the score, like Threefoot (dancer; ed) you are the precise one, or Julien (dancer; ed.) you are the bad one, is really to ask who is controlling who, and who is more human in the end …”

Let me ask you something else. What is this about the AI having been fed with Greek tragedies?

“Well, it is my impression that the intention of using Greek tragedies was to find some moments which were kind of showing a universal or essential aspect of humanity, because the Greek tragedies translate some essential aspects of our way of relating to each other.”

Like power, passion and jealousy…?

“Yes, I think it showed what the AI could do with these images on stage and how they could relate to each other. How one character can be extracted from one picture to leave something else with someone else and working with this to create some sort of a map of what a life can be in terms of feelings and passion and let the AI guide us through those things, and this is where the part with Shubert is coming in and the dancers take over.”

The dancers also take over a bit when it comes to the images of the classical sculptures, right? I mean the sculptures like of The hunter, or the last thing maybe is a sculpture of Jesus, where the AI says: No, we didn’t agree to this?

“Yes, that is a kind of a protest from our part, where the AI, is losing control, which is kind of funny, and this is where I think, we could go a bit further, but that is my personal opinion. It could have been so nice that it went so far that at some point we disagree with the AI.”

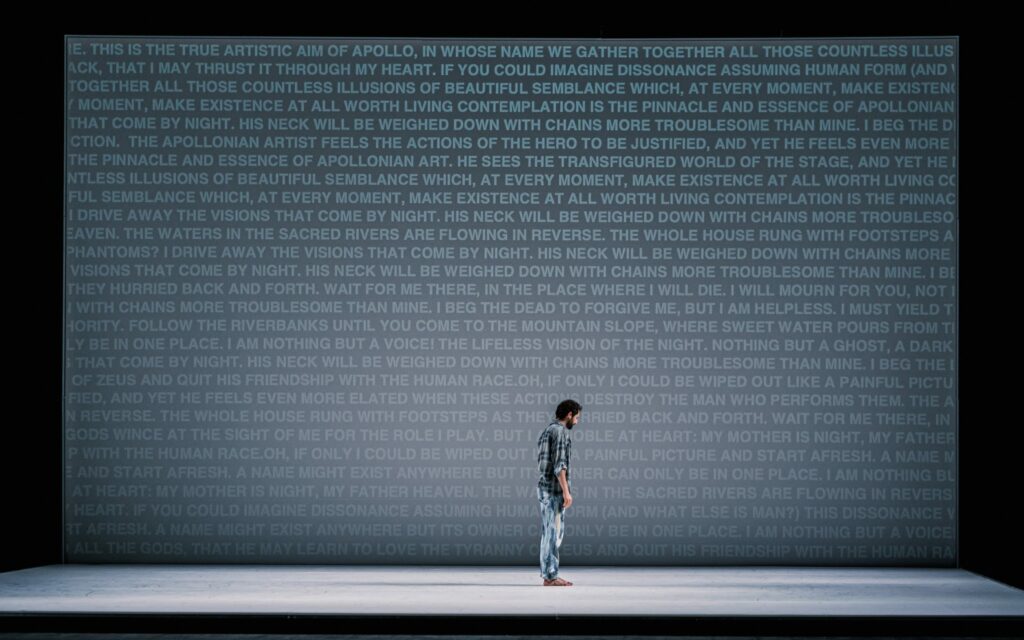

There is also this moment where the AI is telling the solo dancer, with whom he is doing a dance, to let himself be guided by the AI?

“Yes, in a way he is being guided, but at some point it is just like he thinks: What’s the point of being guided? There is this thing, where I want to be recognized as a human, not as a tool … and the entire end is also to show that, I think. Maybe Pontus will disagree with that, but there is this moment where after this happens, when the AI is telling the dancer doing the solo part, like: Hey, I’m made of humans. I am all the humans around you. At the end of the day, I am not using you as a tool, because I am also like you. I’m made by you.”

How do you feel about that question? Like in the case of Watson, a medical robot, it is only what you feed him with that he can process or use …

“Ah, that is a good question. I think it has to do with how much you let the AI guide you. We have a tendency to think that the AI knows better than us, and that the AI is more reliable. I think Centaur is an invitation to remember that we are humans in the end, and that we can disagree. Because at the end, the dancer, who is being guided by the AI, is walking through the river and disappearing – which is the very last image. I think it is a choice we have, to let ourselves be guided (or steered) by the AI.”

The dancers are wearing these clothes with paint on it, to maybe make them look more humans or like artists, I imagine. Do you think we will use AI even more in the arts in the future?

“Yes, I think it will happen. Like already Cecilie Waagner Falkenstrøm, the woman that worked on the piece with us, which is the programmer actually of the AI and everything, is an artist in the first place. She is an artist working with AI in the artistic field. Yet I think working on Centaur shows the limit of wanting to make connections between AI and humans. Even though the AI was the latest version, we had to compromise, because the AI is a kind of unable to fix problems for example that happen because of our failures as humans.

You have been touring with Centaur, right?

“We have been touring a lot with Centaur and each time we perform, I think it requires much more preparation than for a normal show, because we have to remember not only the steps. We have to remember how to respond to the AI and how to interpret what the AI says, and finding this balance between being super prepared, but also being ready to be extremely spontaneous.”

So do you consider that the biggest challenge?

“This is funny, because it is a very tiring performance. However, it isn’t the most physically tiring experience. There is this part, where we pass and pass again across the stage. This part is very physically tiring but it is a very short moment. I think Sirene for instance, which is another piece of Pontus, is a bit more physical in a way and more technical, but I am much more exhausted after Centaur than after Sirene.”

Did you get to add some of your own moves?

“A lot of movements came from us dancers, and were freely created, but in the composition it became very methodic. In Centaur it was to some extent about how to be efficient and clever to make something the AI will understand, and that we will be able to perform. Using the human error to create is interesting, and I think it is a lot how we create in general in the studio. It is letting mistakes become something. That wasn’t so much the case with Centaur.”

Did you bring less emotions into the piece?

“We have to follow some kind of logic, in the sense that we have to put our feelings a little bit aside. In the performance itself it is actually a kind of a challenge to be ourselves, when the AI is telling us what to do. Do we respond by laughing or do we feel embarrassed? In some parts, we have to shut our feelings down, and that was kind of a challenge – to jump in and out of ourselves in a way. The entire piece is about being humans who play the game of the AI. In that sense we are all the time flirting with the border between being ourselves and playing the role the AI gave us.”

The views and interpretations expressed in this interview do not necessarily entirely reflect the views and interpretations of Dansk Danse Teater

More information: Dansk Danseteater